[ad_1]

A sewage therapy plant in Norfolk, Va., is likely one of the websites the place employees accumulate wastewater samples to check for COVID tendencies within the close by group.

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

cover caption

toggle caption

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

A sewage therapy plant in Norfolk, Va., is likely one of the websites the place employees accumulate wastewater samples to check for COVID tendencies within the close by group.

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

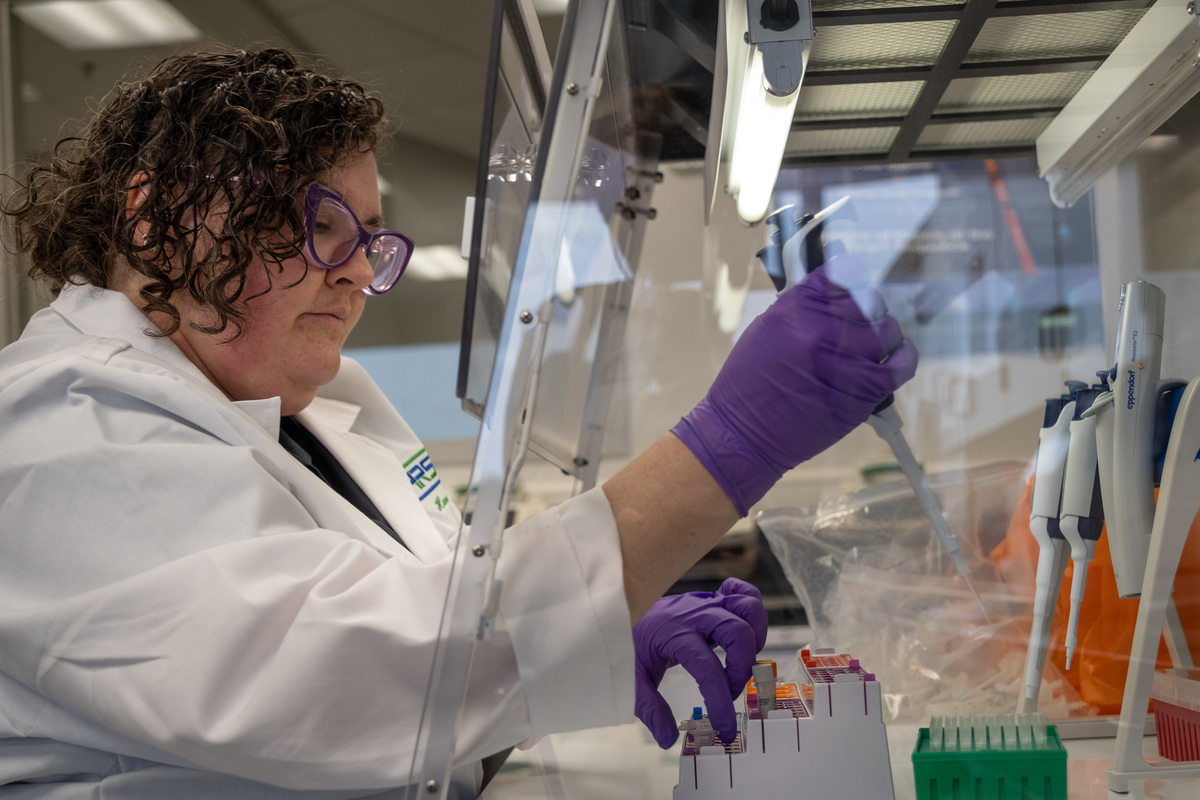

VIRGINIA BEACH, Va. – The perfect time of day to gather a wastewater pattern is within the morning. That is in accordance with Raul Gonzalez, an environmental scientist who’s an skilled on how folks’s hygiene habits intersect with the move of sewage.

Gonzalez runs the wastewater surveillance program on the Hampton Roads Sanitation District, a Virginia Seaside, Va., sewage therapy operation that processes waste for 20% of the state’s inhabitants. He and his staff had been early adopters of wastewater surveillance – a approach of monitoring the focus of viruses, micro organism and infectious illnesses in sewage to look at for infectious illness outbreaks.

Since March 2020 – months earlier than the Facilities for Illness Management and Prevention launched a nationwide initiative – Gonzalez and his colleagues have been monitoring COVID ranges within the sewage that comes by their crops.

Wastewater — from close by houses, companies, bogs and sinks — finally ends up on the Virginia Initiative Plant in Norfolk, Va., the place it will get routed by numerous levels of therapy earlier than being launched into the Chesapeake Bay.

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

cover caption

toggle caption

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

Wastewater — from close by houses, companies, bogs and sinks — finally ends up on the Virginia Initiative Plant in Norfolk, Va., the place it will get routed by numerous levels of therapy earlier than being launched into the Chesapeake Bay.

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

Notes

Wastewater oxidizes in one of many tanks on the therapy facility.

Wastewater knowledge is a helpful complement to the standard metrics of circumstances, hospitalizations and deaths, well being consultants say. The info do not rely on folks in search of out testing or labs reporting outcomes. As an alternative, it depends on folks’s day by day habits, and the truth that folks carrying the virus will shed it once they poop. It identifies broad tendencies shortly, and can be utilized to check for different pathogens like flu, polio, mpox and antibiotic-resistant micro organism.

How wastewater surveillance occurs

How does a bit of the virus that causes COVID from somebody’s intestine move from their rest room to the sewage therapy plant — and find yourself as a knowledge level on a COVID dashboard? On the Hampton Roads Sanitation District, it takes two days and the labor of many individuals. All of it begins with a pattern gathered early within the day, to catch folks’s morning poops.

Marcos Davila-Banrey and Jon Nelson put together to seize a wastewater pattern for the Hampton Roads Sanitation District COVID surveillance program.

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

cover caption

toggle caption

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

Marcos Davila-Banrey and Jon Nelson put together to seize a wastewater pattern for the Hampton Roads Sanitation District COVID surveillance program.

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

Nelson lifts a sterile plastic bottle on the finish of a pole full of murky wastewater. The water pattern he retrieves will turn into helpful info on the degrees of COVID within the close by group.

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

cover caption

toggle caption

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

On a latest, grey day at a therapy plant in Norfolk, Gonzalez’s colleague Jon Nelson stood over a small metallic hatch that opened onto a pipe of incoming sewage. He put a sterile plastic bottle on the finish of a protracted pole extra usually used to carry a paint curler, and lowered it about 18 toes into the river of wastewater coming from the area’s houses, campuses and companies.

By the point it will get to the plant, sewage smells just a bit sulfurous and it is not brown, however a murky grey. “It appears to be like nothing like what you see in the bathroom,” says Joshua Coyle, an operations lead on the plant – within the journey by the pipes, “[the fecal matter] all dissolves and breaks down.”

As soon as the wastewater is bottled, it turns into a treasured pattern. It is chilled in a cooler of ice, to maintain it contemporary for the 20-minute drive to the labs on the sewage utility’s headquarters.

It is a ritual the staff has performed each week for the previous three years – not simply at this one plant however on the eight they handle, protecting 5,000 sq. miles in southeast Virginia.

Raul Gonzalez, at a Hampton Highway Sanitation District lab in Virginia Seaside, Va. He leads the district’s wastewater surveillance program which started monitoring COVID ranges in March 2020.

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

cover caption

toggle caption

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

This system took loads of “blood, sweat and tears” to face up, Gonzalez says, recalling the early, unsure days of the COVID pandemic and the experimentation it took to search out dependable methods to measure COVID within the wastewater. Now, they have their course of dialed in.

Cleansing up sewage samples again within the lab

On the sewage utility headquarters, the pattern passes by three adjoining laboratories and several other workers to get the virus filtered out of the sewage water, cleaned after which counted.

Notes

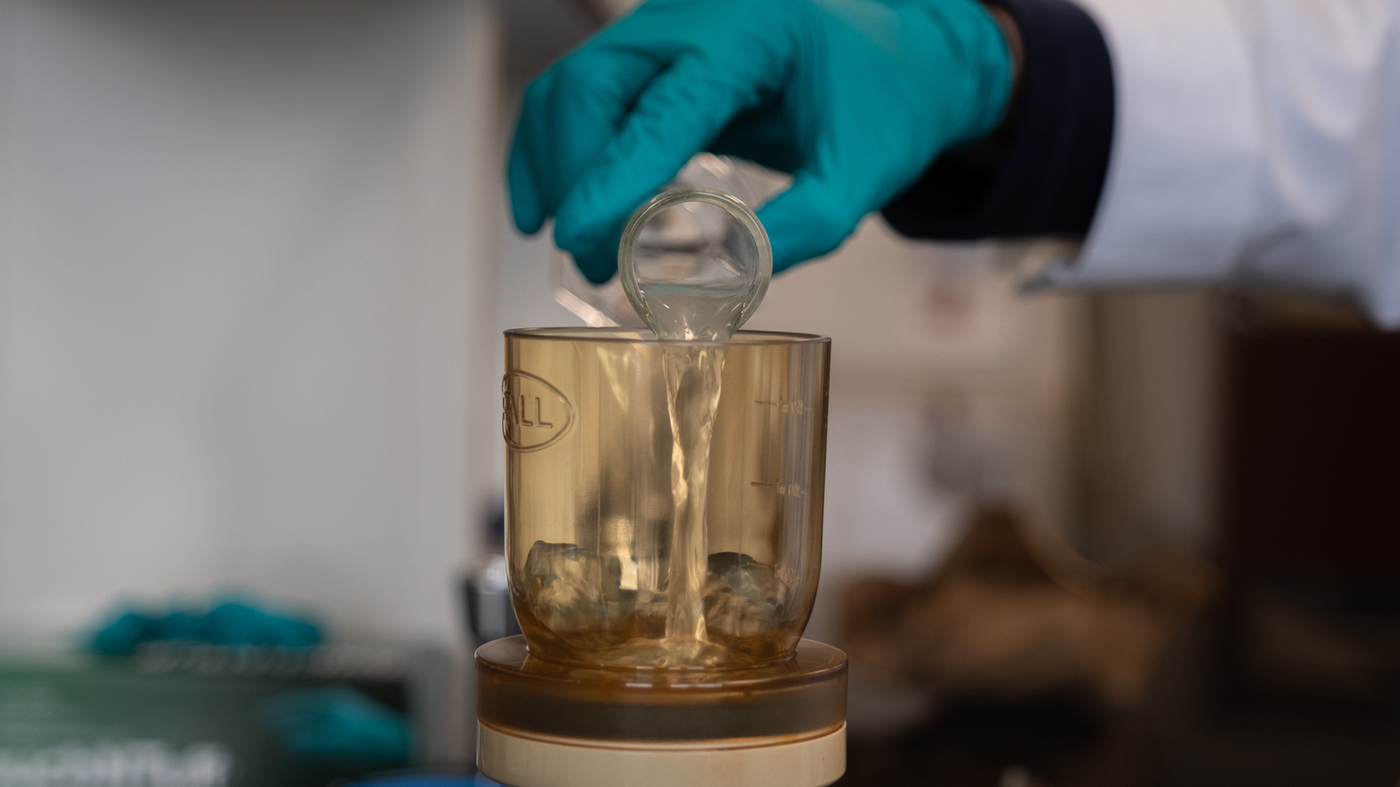

When the wastewater arrives on the lab, acid is added to positively cost virus particles within the pattern.

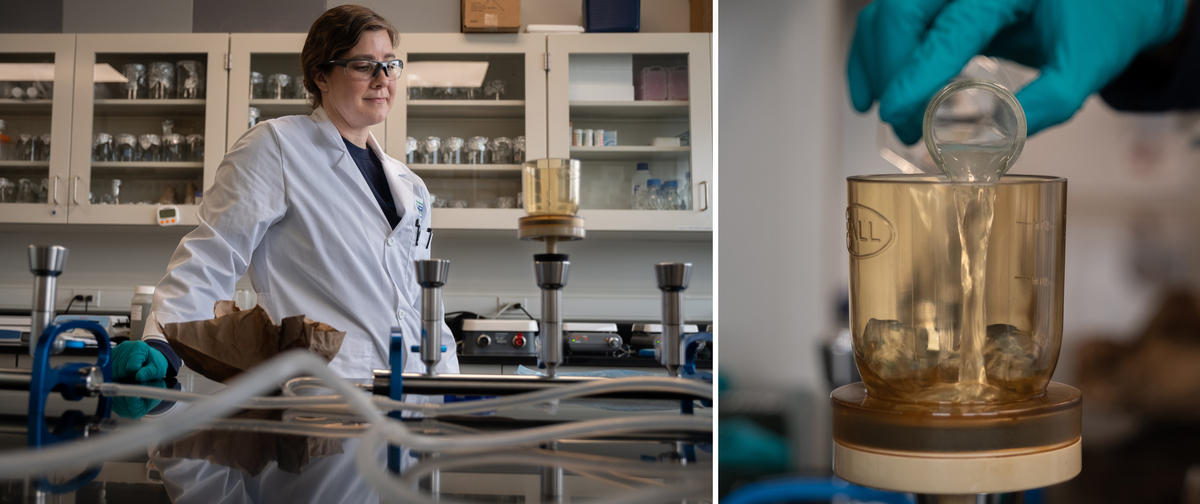

Kat Yetka (left) pours the wastewater pattern over a filter (proper), negatively-charged to raised seize COVID virus particles, at a Hampton Highway Sanitation District lab in Virginia Seaside, Va.

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

cover caption

toggle caption

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

Kat Yetka (left) pours the wastewater pattern over a filter (proper), negatively-charged to raised seize COVID virus particles, at a Hampton Highway Sanitation District lab in Virginia Seaside, Va.

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

Step one is to go a few of the liquid from the bottle by a paper filter, which helps separate the virus from the sludge within the water. Workers scientist Kat Yetka provides acid to the pattern to positively cost the virus particles, in order that they’re extra more likely to keep on with the negatively-charged filter. It takes just some minutes. The pattern has gone from a one-liter bottle of liquid, to a small paper filter, in regards to the width of an Oreo cookie. Yetka folds it with forceps and sticks it in a take a look at tube.

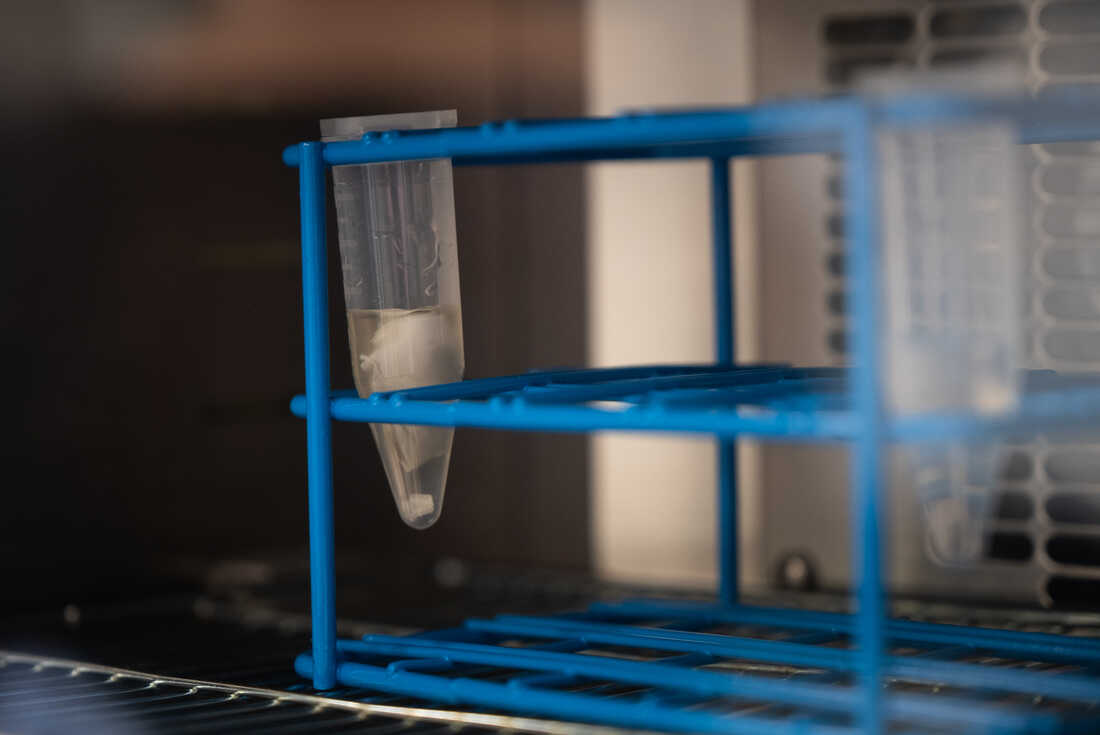

The filter soaks in a small vial as a part of the method.

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

cover caption

toggle caption

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

The filter soaks in a small vial as a part of the method.

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

That filter will get bathed in chemical substances to launch the viral RNA from cells within the pattern, after which to scrub away poop and different detritus. “[We’re washing] every little thing from solids to natural supplies to salts out of the pattern,” Gonzalez says, “We’re making an attempt to scrub up every little thing however the targets we’re on the lookout for.”

As soon as the pattern is as clear as it should be — it is time to begin quantifying how a lot virus the researchers have collected.

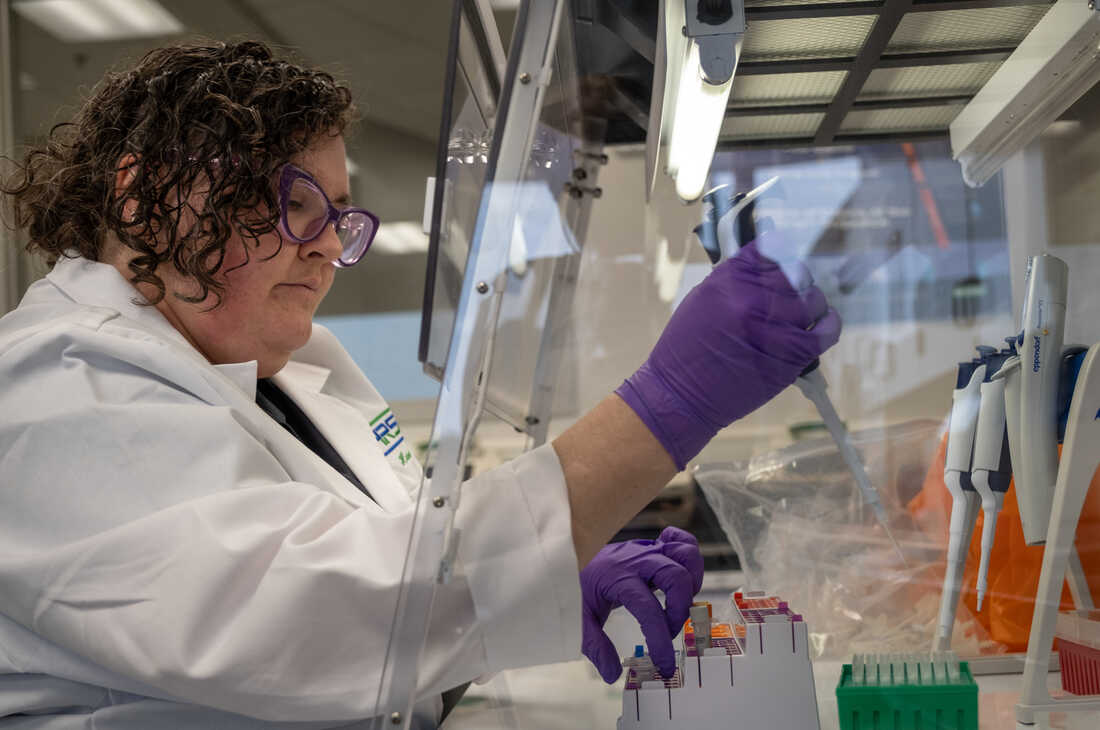

Hannah Thompson, a microbiologist on the lab, provides a fluorescent dye to the pattern, which glows when it attaches to the COVID virus. She takes a little bit of the handled liquid — in regards to the dimension of a raindrop — and breaks it down into many smaller droplets. It is the ratio – of droplets which have COVID in them, versus those who do not – that may function the idea for determining how a lot virus is within the complete pattern.

She then places the droplets right into a machine that makes copies of the virus’ genetic code “by 40 cycles of heating and cooling, heating and cooling” she says, so the degrees might be excessive sufficient to measure.

“By the tip, we’ll have billions of copies,” Thompson says. The method takes a number of hours, in order that they set it to run in a single day.

Hannah Thompson mixes probes and primers that she provides to the pattern to assist determine COVID within the water. The purpose is to run these by a machine that may amplify any COVID within the liquid.

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

cover caption

toggle caption

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

Hannah Thompson mixes probes and primers that she provides to the pattern to assist determine COVID within the water. The purpose is to run these by a machine that may amplify any COVID within the liquid.

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

Right here in Virginia Seaside, processing a single wastewater pattern takes two days and a number of expert employees. This is not the method in every single place – some sewage crops accumulate samples that they then ship off to state well being departments or the CDC’s federal contractors to course of.

And lots of crops do not take part in any respect – it is fully voluntary. The CDC says that nationally, the wastewater surveillance program they coordinate covers round 40% of the U.S. inhabitants.

Along with analyzing their very own wastewater, Gonzalez’s staff additionally sends some samples to Virginia’s well being division and the CDC. Nonetheless, he says his staff is continuous its personal efforts in-house as a result of it creates a constant document courting again to the beginning of the pandemic, and it is helpful for his or her native well being departments.

Early the subsequent morning, Gonzalez is again on the lab with Hila Stephens, a molecular biologist, who runs the plate with the droplets by a machine to determine how a lot COVID was within the pattern.

“I am betting my cash on a pattern that is been going for awhile,” Stephens says, “So there will be some COVID within the water.” She is correct. The quantity of COVID within the water that week in March is about the identical because it was the week earlier than.

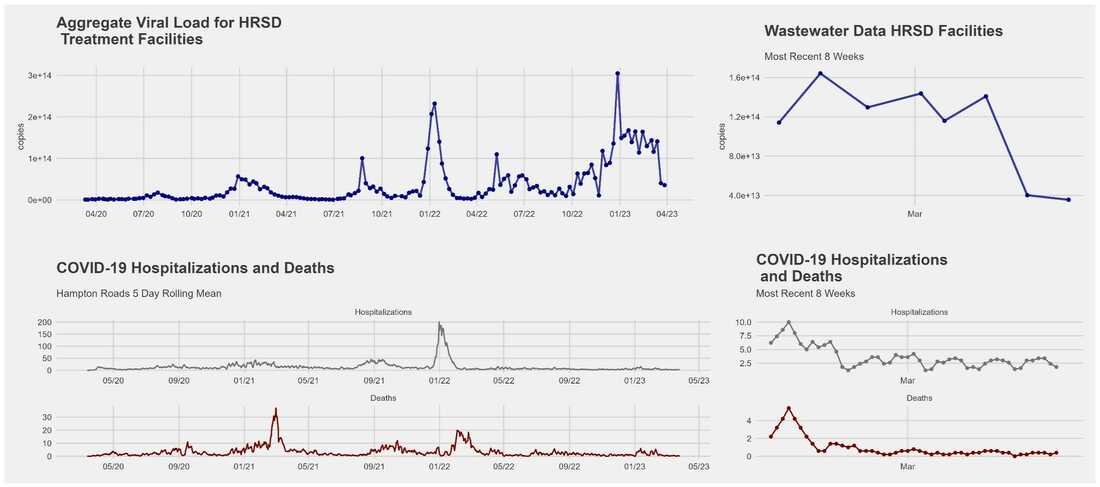

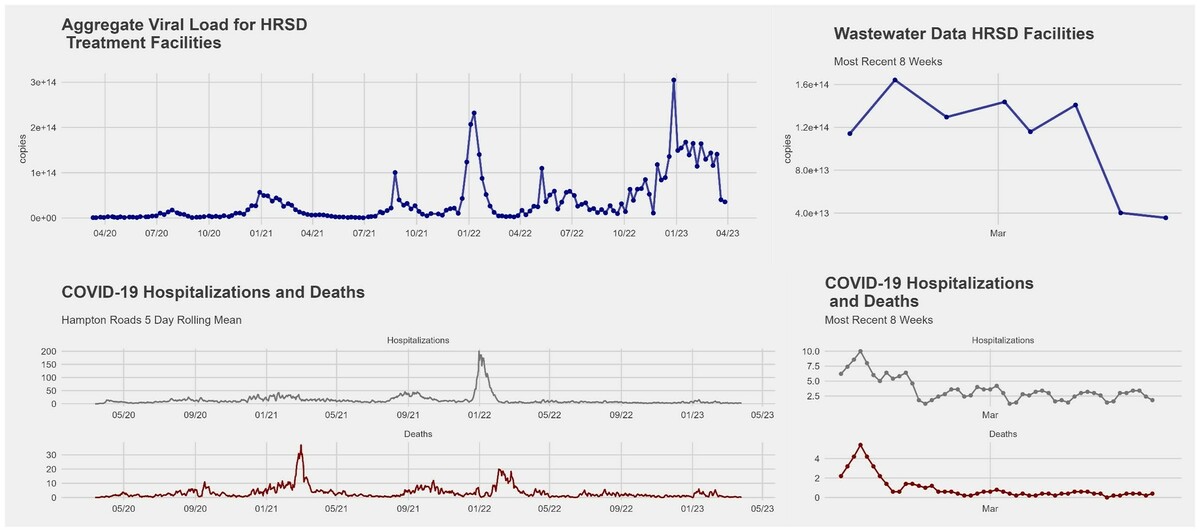

The sewage knowledge drives a public well being dashboard

The info will get shared on a public dashboard. Kyle Curtis, Gonzalez’s fellow environmental scientist on workers, runs the numbers by a pc script to visualise how the degrees are trending. Regardless that the virus degree are excessive (as of this studying in March), hospitalizations and deaths are as little as they have been this entire pandemic.

“I believe we have a look at it with completely different eyes than we used to,” Curtis says. “In earlier waves, we did not know what the ceiling [of infections and serious illness] seemed like for the group.” Now, the broad degree of immunity from vaccinations and former infections implies that excessive ranges of COVID do not essentially forecast many COVID deaths.

Gonzalez and his staff use the surveillance knowledge they accumulate to trace general tendencies in COVID infections. The data is made out there on a public dashboard alongside hospitalizations and deaths with the intention to give a fuller image of the well being of the group.

HRSD/Screenshot by NPR

cover caption

toggle caption

HRSD/Screenshot by NPR

Gonzalez and his staff use the surveillance knowledge they accumulate to trace general tendencies in COVID infections. The data is made out there on a public dashboard alongside hospitalizations and deaths with the intention to give a fuller image of the well being of the group.

HRSD/Screenshot by NPR

Nonetheless, public well being officers say these tendencies are essential to trace.

“None of those single knowledge factors are excellent,” says Dr. Caitlin Pedati, head of the Virginia Seaside Division of Public Well being. “But when I have a look at my wastewater tendencies along with hospitalization knowledge and what is going on on in nursing houses, amongst high-risk services and populations, that is going to offer me a good sense of whether or not exercise goes up, taking place or staying the identical.”

That in flip might be used to assist her decide the place and when to supply COVID testing or vaccine clinics for folks at larger threat from COVID.

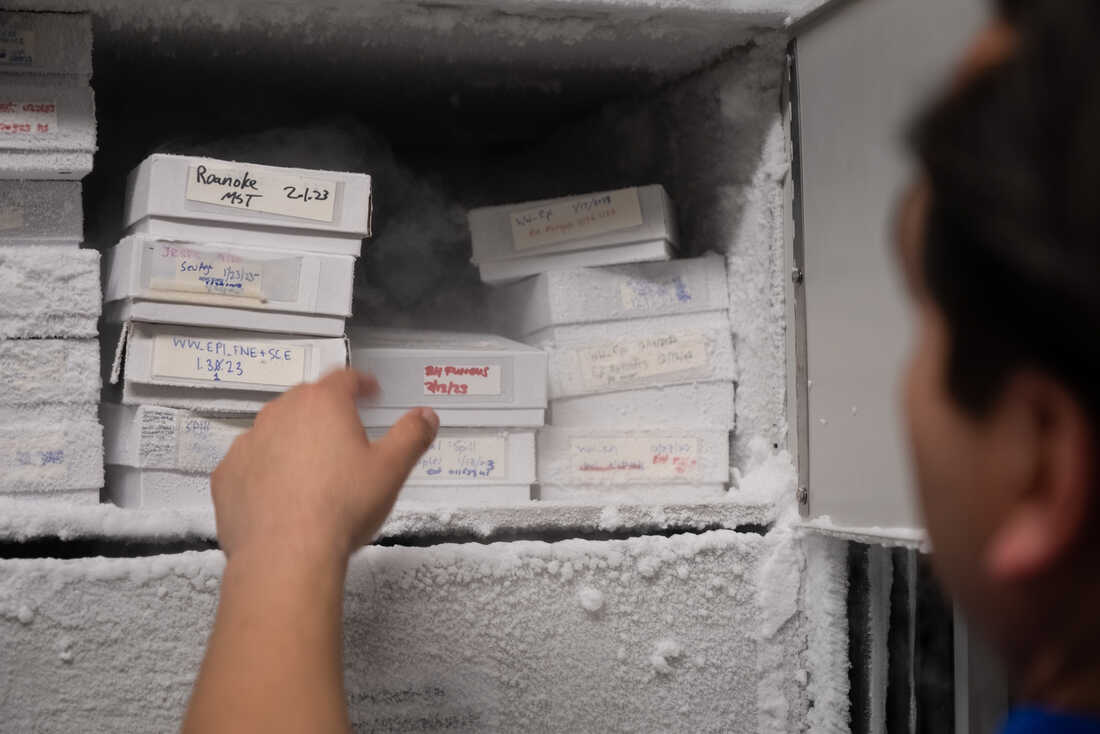

Wastewater surveillance obtained loads of consideration and funding throughout COVID. Many public well being officers hope that is simply the beginning. “We’re within the technique of increasing [wastewater surveillance] to an entire suite of different pathogens, from influenza and RSV to norovirus and E. coli,” says Amy Kirby, who leads the CDC’s nationwide wastewater surveillance program.

She envisions a future the place the info function an early warning for public well being officers, and as a “well being climate report” for communities, the place folks may test a dashboard displaying pathogen tendencies of their space, and use it to resolve whether or not to put on a masks, or take precautions whereas touring, or to take additional care cooking their meals or washing their arms.

Gonzalez’s staff shops a small portion of their wastewater samples within the freezer. Many public well being officers hope that the eye and funding for COVID surveillance in the end extends to different pathogens too, like monitoring RSV or norovirus infections.

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

cover caption

toggle caption

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

Gonzalez’s staff shops a small portion of their wastewater samples within the freezer. Many public well being officers hope that the eye and funding for COVID surveillance in the end extends to different pathogens too, like monitoring RSV or norovirus infections.

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

However Gonzalez says it takes loads of time and assets to maintain it going. He is a part of a committee on the Nationwide Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Drugs urging extra funding for the nationwide program. Up to now, the federal authorities has spent $300 million on wastewater surveillance, and is dedicated to spending one other $320 million to broaden this system by 2025.

The system may function an early warning sign in a future pandemic. “We have invested quite a bit to construct this method, and it might be tough to close it down and begin it up once more,” Kirby says, “It is rather more cost-efficient to maintain it working.” However, she says, it requires continued funding to make that actual.

Images and visuals manufacturing by Meredith Rizzo. Enhancing by Scott Hensley.

[ad_2]