[ad_1]

Fred Crittenden, 73, misplaced his sight to retinitis pigmentosa when he was 35 years outdated. At the moment he has no visible notion of sunshine. “It is whole darkness,” he says. Nonetheless, he has cells in his eyes that use gentle to maintain his inner clock ticking alongside properly.

Marta Iwanek for NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Marta Iwanek for NPR

Fred Crittenden, 73, misplaced his sight to retinitis pigmentosa when he was 35 years outdated. At the moment he has no visible notion of sunshine. “It is whole darkness,” he says. Nonetheless, he has cells in his eyes that use gentle to maintain his inner clock ticking alongside properly.

Marta Iwanek for NPR

Each baseball season, 73-year-old Fred Crittenden crops himself in entrance of his tv in his small one-bedroom condo an hour north of Toronto.

“Oh, I like my sports activities — I like my Blue Jays,” says Crittenden. “They want me to teach ’em — they’d be successful, I am going to inform ya.” He listens to the video games in his condo. He does not watch them, as a result of he cannot see.

“I went blind,” Crittenden remembers, when “I used to be 35 years younger.”

Crittenden has retinitis pigmentosa, an inherited situation that led to the deterioration of his retinas. He misplaced all his rods (the cells that assist us see in dim gentle) and all his cones (the cells that permit us see coloration in brighter gentle). Inside a single 12 months, in 1985, Crittenden says he went from excellent imaginative and prescient to whole blindness.

Sure cells inside Crittenden’s retinas that comprise melanopsin assist his mind to detect gentle, even when what he sees is darkness. Amongst different issues, these light-detecting cells assist his physique regulate his sleep cycles.

Marta Iwanek for NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Marta Iwanek for NPR

Sure cells inside Crittenden’s retinas that comprise melanopsin assist his mind to detect gentle, even when what he sees is darkness. Amongst different issues, these light-detecting cells assist his physique regulate his sleep cycles.

Marta Iwanek for NPR

“The very last thing I noticed clearly,” he says, pondering again, “it was my daughter, Sarah. She was 5 years outdated then. I used to go in at evening and simply take a look at her when she was within the crib. And I might simply barely nonetheless make her out — her little eyes or her nostril or her lips or her chin, that form of stuff. Even to today it is onerous.”

Crittenden says it took him a couple of 12 months to come back to phrases together with his blindness. At the moment, greater than 35 years later, he does not see gentle. “It is whole darkness,” he reviews. Nonetheless, he manages simply superb. There’s a lot he does not need assistance with — together with syncing up with the 24-hour day/evening cycle.

Crittenden takes a stroll close to his house in Sutton West, Ontario.

Marta Iwanek for NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Marta Iwanek for NPR

Crittenden takes a stroll close to his house in Sutton West, Ontario.

Marta Iwanek for NPR

Publicity to gentle is the essential driver in modulating circadian rhythms for most individuals. However different components, together with train, temperature and social interplay, can affect your inner clock, too.

Marta Iwanek for NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Marta Iwanek for NPR

Publicity to gentle is the essential driver in modulating circadian rhythms for most individuals. However different components, together with train, temperature and social interplay, can affect your inner clock, too.

Marta Iwanek for NPR

At evening, Crittenden listens to sports activities or his speaking ebook machine. He is asleep by 11, and off the bed each morning about 6:30, no alarm wanted. That will not appear exceptional, besides that our circadian clocks are deeply influenced by gentle.

Marla Feller, a neurobiologist on the College of California, Berkeley, says, “For those who by no means noticed any gentle, you’ll slowly shift your sleep cycle so that you simply’d begin falling asleep later and later. However what occurs is, every single day you exit and take a look at the solar — and it entrains this circadian clock to be on the 24-hour cycle.”

So Crittenden is one thing of a thriller. He is blind, however his inner clock marches to the 24-hour beat of a sunlit world, give or take a couple of minutes. This is not the case for all people who’re blind. So what is going on on with him?

This brings us to Iggy Provencio, a biologist on the College of Virginia who, in grad faculty within the ’90s, was finding out the African clawed frog. “The frog can be a disgusting-looking animal,” he chuckles. “It has very slimy pores and skin.”

That pores and skin accommodates cells that darken with pigment once they detect gentle, which helps the frogs mix in with the streambed under. Provencio found the molecule accountable for the sunshine detection, which he referred to as melanopsin. And it wasn’t simply within the frog’s pores and skin. He and his workforce discovered it within the retina of the frogs, and of mice too.

“We have been trying by the microscope,” Provencio remembers, “and I instructed my colleague who was with me, ‘We’re the primary folks on the planet to truly view a very novel sensory system in mammals’ ” — together with people.

Melanopsin is not in our rods or cones. Somewhat, it is inside massive neurons referred to as melanopsin cells, that are parked in a unique layer of the retina. “Think about an octopus with its tentacles reaching out,” says Michael Do, a neurobiologist at Boston Kids’s Hospital and the Harvard Medical College. “The melanopsin cells — their arms attain out and overlap with the arms of different melanopsin cells to type a mesh over the retina.”

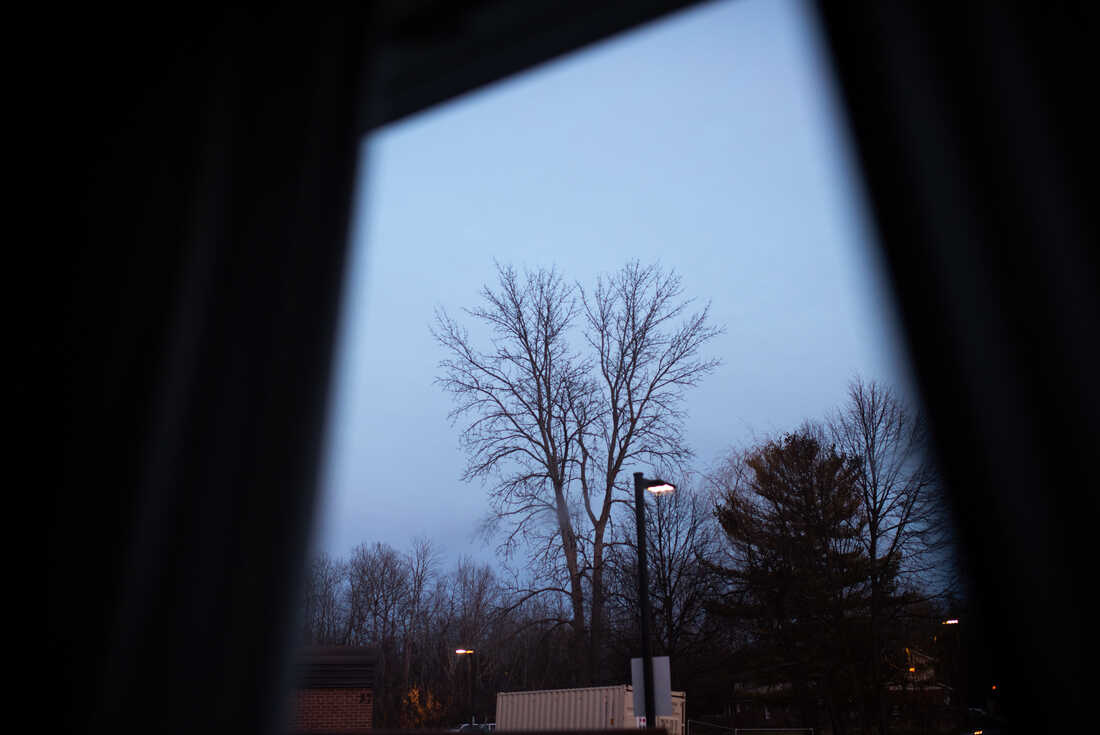

The night gentle from Crittenden’s window casts a faint glow in his condo.

Marta Iwanek for NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Marta Iwanek for NPR

The night gentle from Crittenden’s window casts a faint glow in his condo.

Marta Iwanek for NPR

Dim gentle displays off a mug (left) and a clock on the wall in Crittenden’s house.

Marta Iwanek for NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Marta Iwanek for NPR

Dim gentle displays off a mug (left) and a clock on the wall in Crittenden’s house.

Marta Iwanek for NPR

Your entire mesh is delicate to gentle, particularly brilliant, blue gentle. The solar makes a number of that gentle, as, to a lesser extent, do our telephones, tablets, screens and another indoor lights, streetlights and headlights. The tentacles of these melanopsin cells radiate throughout our brains.

“I feel it is one thing like 30 mind areas are contacted instantly by these cells,” says Do. “One place is the construction on the base of the mind that’s our grasp circadian clock.” It is referred to as the suprachiasmatic nucleus, and it makes use of the sunshine info fed to it by melanopsin cells to instruct the remainder of our physique when it is time to sleep and when it is time to get up. The melanopsin cells additionally assist affect starvation, temperature management, migraine ache and possibly even our temper and the way we study.

Satchin Panda, a chronobiologist on the Salk Institute, says there have been lab experiments the place mice had their melanopsin switched off. “These mice, they’ll sense gentle to some extent,” he says, however issues are off kilter.

For example, give them a lab-mouse model of jetlag — the place someday, you immediately shift when the lights get turned on and shut off — and “these mice, as an alternative of taking seven days to reset to the brand new time zone, they are going to take a month,” Panda says. (There’s variability within the system, which is why some folks have a tougher time adjusting to sunlight saving time or a change in time zones than others.)

So that is the thriller we began with, solved: Fred Crittenden has no functioning rods or cones, however, he does have melanopsin cells.

Crittenden spends time together with his fiancée Carol Tromba on a Saturday afternoon in December.

Marta Iwanek for NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Marta Iwanek for NPR

Crittenden spends time together with his fiancée Carol Tromba on a Saturday afternoon in December.

Marta Iwanek for NPR

Crittenden’s expertise affords perception into an necessary system within the mind and retina (past rods and cones) that’s maintained in sure people who find themselves blind. This method of particular melanopsin cells is probably going what permits Crittenden’s mind to make use of gentle to assist synchronize his inner clock.

It is these cells that inform his physique to start out a brand new day each morning — to verify he is awake when Sarah, his daughter (who’s 42 now) offers him a name.

“She normally calls me each different day, to see how I am doing and that form of stuff,” Crittenden says fondly. “She’s a superb woman.”

Once we spoke, Crittenden had a photograph of Sarah in his condo. In it, she’s smiling. The picture was hanging in his bed room, reverse the window. And on a transparent day, a shaft of daylight would flash by that window and lightweight up Sarah’s face.

This story is a part of our periodic science sequence “Discovering Time — a journey by the fourth dimension to study what makes us tick.”

One other model premiered throughout a dwell present in 2016 on the Charles Hayden Planetarium on the Museum of Science, Boston.

[ad_2]